India’s EV Boom Is Real, but the Hardest Miles Lie Ahead

India’s electric vehicle story has crossed an important psychological threshold. What was once dismissed as aspirational, experimental or premature has begun to look inevitable. On congested city roads where exhaust fumes and impatience once dominated, scooters now glide silently through traffic, electric rickshaws hum instead of rattle, and charging cables sprawl across depots that once smelled of diesel.

The shift is no longer anecdotal. India’s electric vehicle market is finally gathering speed, and the numbers make that clear. In the financial year 2024–25 alone, the country sold more than 2 million electric vehicles, according to industry estimates. Today, nearly 6.5 million EVs operate on Indian roads, a milestone that would have seemed improbable just a few years ago.

In the April–June 2025 quarter, EV sales rose 34 percent year-on-year, capturing around 8 percent of overall vehicle sales. Yet, unlike many Western markets where electric adoption is led by premium passenger cars, India’s EV revolution is unfolding at the mass-market level, driven by mopeds, rickshaws and buses rather than luxury sedans.

This distinction may well define India’s advantage, even as the road ahead remains challenging.

India’s EV Market Is Built on Mopeds and Rickshaws

To understand India’s EV boom, it is essential to look beyond passenger cars. More than half of all EV sales in India come from two-wheelers, with battery-powered scooters and motorcycles becoming the default choice for daily commuters. Rising fuel prices, short urban commutes and lower running costs have made electric two-wheelers particularly attractive in densely populated cities.

Another 36 percent of EV sales come from three-wheelers, a category in which India has quietly become a global leader. In fact, electric vehicles now account for over 57 percent of all three-wheeler sales, a penetration rate that far outpaces most large economies.

For auto-rickshaw drivers and last-mile delivery operators, the decision is largely economic. Electric three-wheelers cost less to operate, require minimal maintenance and offer predictable daily expenses. In a country where millions depend on such vehicles for livelihoods, the EV value proposition is compelling and immediate.

Passenger Cars Lag Behind, for Now

Electric passenger cars, by contrast, remain a smaller piece of India’s EV puzzle. In 2025, electric cars accounted for just 5 percent of total car sales, up modestly from 2–4 percent in earlier years.

This segment is dominated by domestic manufacturers such as Tata Motors and Mahindra, along with newer entrants like MG Motor. While interest is growing, high upfront costs, limited model options and uneven charging infrastructure continue to restrain mass adoption.

Overall, EV penetration across all vehicle categories now stands at around 7–8 percent. While encouraging, this remains well short of the government’s ambitious target of 30 percent EV penetration by 2030.

Why India’s EV Push Matters

Behind India’s EV momentum lies a combination of urgency and opportunity. India is the world’s third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, and its cities routinely rank among the most polluted globally. Delhi, in particular, continues to experience hazardous air quality levels, forcing authorities to impose restrictions on construction and vehicle movement.

Electrifying transport is therefore not viewed merely as a technological upgrade, but as a public health intervention and a cornerstone of India’s net-zero ambitions. This logic has shaped government policy, leading to subsidies, production-linked incentives and mandates for public procurement.

Policymakers are not only targeting 30 percent EV penetration by 2030, but even higher electrification levels for buses, two-wheelers and three-wheelers. If these targets are achieved, annual EV sales could reach 17 million units by the end of the decade, potentially pushing the market value beyond $100 billion.

Electric Buses Make the Strongest Economic Case

Nowhere is the economic argument for electrification clearer than in public transport. Electric buses already account for roughly one-fifth of new city bus orders, and their operational advantages are hard to ignore.

Over a typical 12-year lifecycle, electric buses can save operators hundreds of thousands of dollars per vehicle due to lower fuel and maintenance costs. For cash-strapped municipal transport agencies, these savings could fundamentally reshape procurement decisions and fleet planning.

As cities expand and urban populations grow, electric buses may become one of the most transformative elements of India’s EV transition.

Infrastructure Gaps Remain a Critical Challenge

Despite rapid sales growth, charging infrastructure remains India’s weakest link. While fast chargers and battery-swapping stations are expanding, coverage remains uneven and reliability varies widely. For many drivers, especially outside major cities, range anxiety remains a real concern.

Experts argue that increasing battery range alone will not solve the problem. What India needs is charging density: a network that is visible, predictable and seamlessly integrated into daily life. Achieving this requires coordination across multiple government agencies, from land allocation and power supply to local permits and grid upgrades.

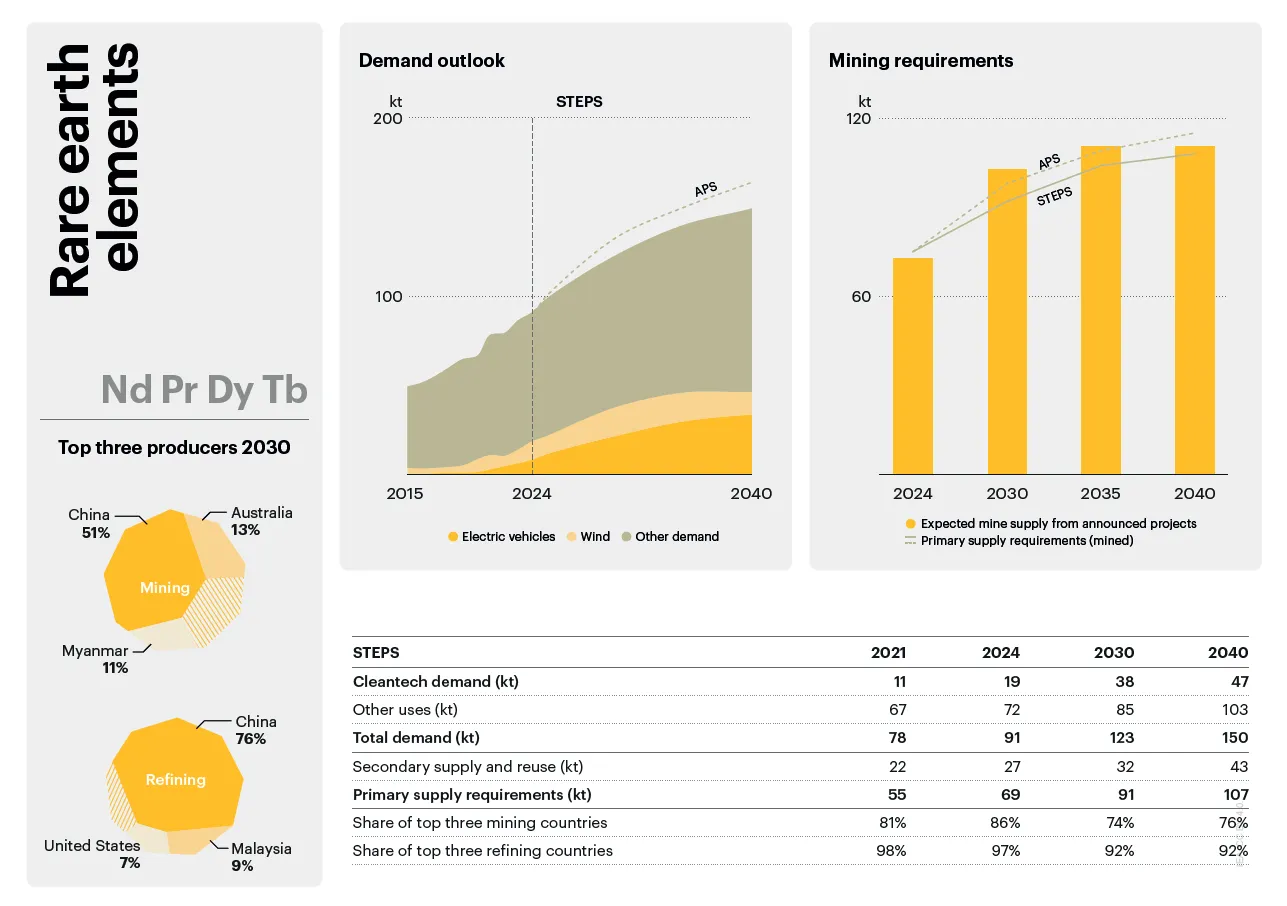

Battery Supply Chains Pose Another Risk

Battery manufacturing presents another vulnerability. India remains heavily dependent on imports for critical minerals, exposing the EV ecosystem to global supply chain disruptions and price volatility.

The government has launched a national mission to secure mineral resources and develop domestic manufacturing capacity, but results will take time. Until then, battery costs and availability will continue to influence EV affordability.

EV Growth Will Be Driven by Fleets, Not Garages

If India’s EV transition succeeds at scale, it is likely to do so through fleets rather than private garages. Electric vehicles already dominate last-mile delivery, quick commerce and high-frequency urban travel, where predictable routes and centralized charging make electrification easier.

Logistics firms and ride-hailing platforms are emerging as powerful catalysts, ordering vehicles by the thousands rather than the dozens. This emphasis on scale over status differentiates India from Western EV markets and could prove to be a long-term advantage.

Awareness and Storytelling Lag Behind

Even as sales climb, consumer awareness remains uneven. Industry leaders point to markets like Vietnam and Indonesia, where large salesforces are dedicated to educating buyers about electric vehicles.

India, by contrast, has leaned more heavily on subsidies than storytelling. The next phase of growth may depend on closing this awareness gap, convincing consumers that electric mobility is not just cleaner, but more practical, reliable and economical.

India’s EV Battery Demand Is Set to Explode

The future of India’s EV market is inseparable from batteries. According to Customised Energy Solutions’ (CES) 2025 EV Battery Technology Review Report, India’s EV battery demand could rise more than 14 times by 2032.

Demand is projected to jump from 17.7 GWh in 2025 to 256.3 GWh by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 35 percent. Rising fuel prices, faster EV launches and supportive national and state policies are driving this surge.

Government measures such as Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFÉ) norms and targeted incentives have played a key role in encouraging both EV adoption and battery manufacturing investment. CES describes this convergence as a turning point for India’s automotive sector.

New Battery Technologies Take Centre Stage

The report highlights rapid advances in battery chemistry. Next-generation lithium-ion batteries, including LFP (lithium iron phosphate) and NCM (nickel cobalt manganese), are improving energy density, safety and cost efficiency.

Notably, LFP Gen 4 cells now exceed 300 Wh/kg, offering longer driving ranges and potential cost reductions. Emerging technologies such as sodium-ion and solid-state batteries are also entering the market, supporting applications from two-wheelers to commercial fleets.

Indian manufacturers like Tata Agratas, Ola Electric and Amara Raja are expanding capacity, while others invest in dual-chemistry and sodium-ion solutions. However, challenges remain, including high capital costs, supply chain risks and import dependence.

The Road Ahead

India’s EV boom is unmistakably real. The hum on its roads is growing louder, and the economic logic behind electrification is strengthening across segments. Yet the hardest miles lie ahead.

Success will depend not just on technology, but on policy coherence, infrastructure buildout, domestic manufacturing and public trust. If India can bridge these gaps, its EV transition may not only transform mobility at home, but also offer a global model for mass-market electrification.