Quick Highlights:

- India’s EV battery recycling market could expand nearly 10-fold by 2030, driven initially by commercial vehicles

- Two-wheelers will be the first major source of end-of-life batteries, followed by commercial four-wheelers

- EPR regulations and geopolitical risks around critical minerals are accelerating recycling investments

- Leading recyclers like Attero are rapidly scaling capacity to meet rising battery volumes

India’s EV Battery Recycling Dreams: From Early Adoption to Circular Economy

India’s electric vehicle (EV) story is no longer just about adoption. With monthly sales of around 1.4 lakh electric two-wheelers, 17,000–18,000 electric three-wheelers, and 15,000–16,000 electric four-wheelers, the country is entering a new phase: managing what happens when these batteries reach the end of their usable life.

As early-generation EVs begin ageing out, India is approaching its first significant wave of retired lithium-ion batteries, creating a defining moment for battery recycling and second-life energy storage companies.

EV Adoption Is Laying the Foundation for Recycling Growth

Even before large-scale battery replacement cycles fully begin, existing EV volumes are already building a strong base for recycling. According to industry estimates, this market could grow nearly ten-fold by 2030, with commercial vehicles leading the early phase.

Utkarsh Singh, Chief Executive of BatX Energies, notes that electric two-wheelers will drive the first surge in recycling volumes, given India’s massive two-wheeler population and their widespread use in daily commuting and gig-economy applications.

He adds that commercial four-wheelers will follow, while buses and heavy commercial vehicles are expected to contribute the largest battery volumes over time, due to their significantly higher battery capacities.

Recyclers Scale Up Ahead of the End-of-Life Wave

Battery recyclers are not waiting for volumes to peak before acting. Companies are already expanding capacity to prepare for the uneven but inevitable influx of end-of-life batteries.

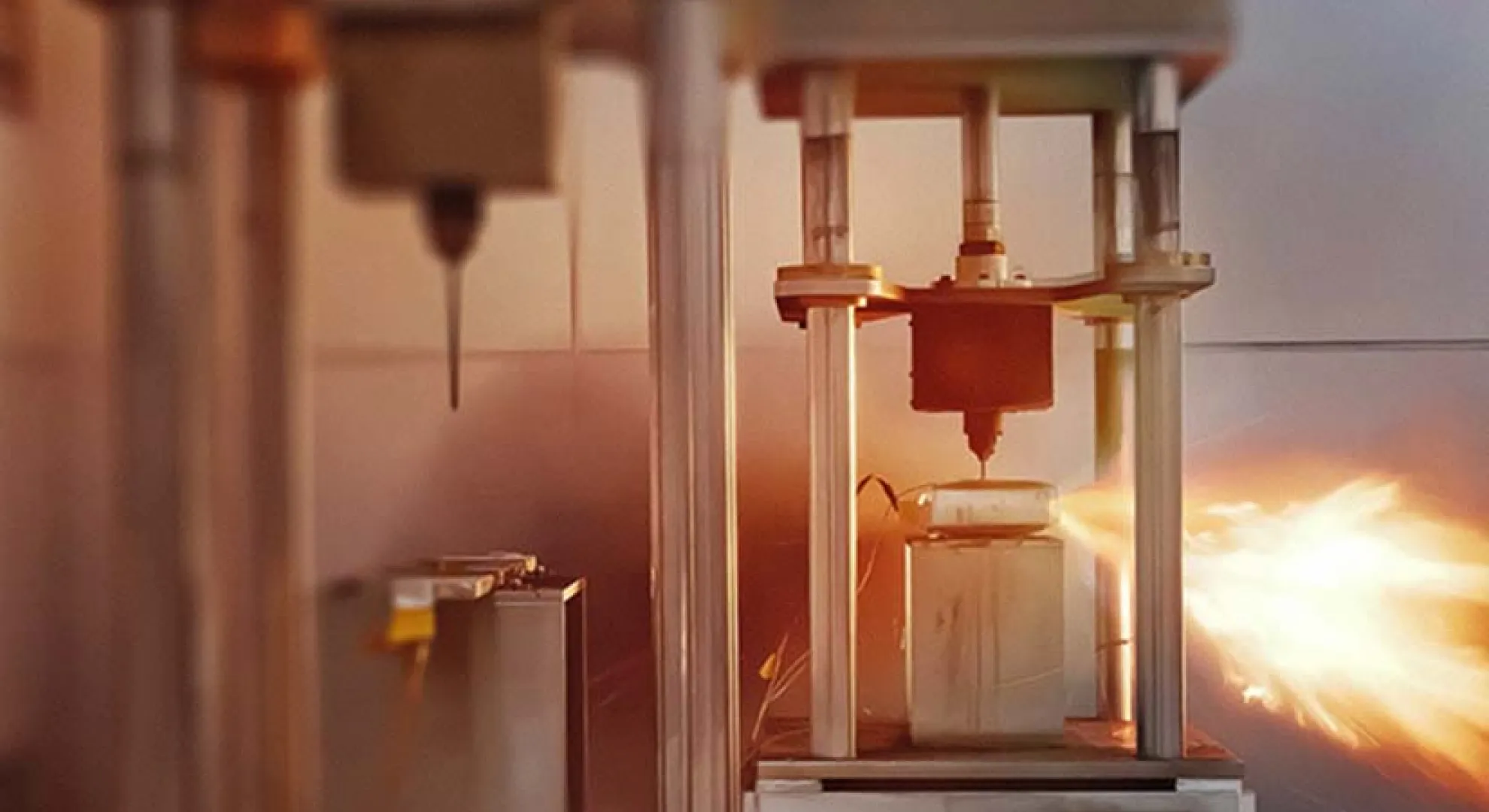

Attero, one of India’s leading electronic waste and lithium-ion battery recyclers, currently extracts more than 22 pure metals through a proprietary combination of mechanical recycling and hydrometallurgical processes. The company recovers battery-grade lithium carbonate, cobalt, nickel, manganese sulphate, and graphite with extraction efficiency exceeding 98 percent.

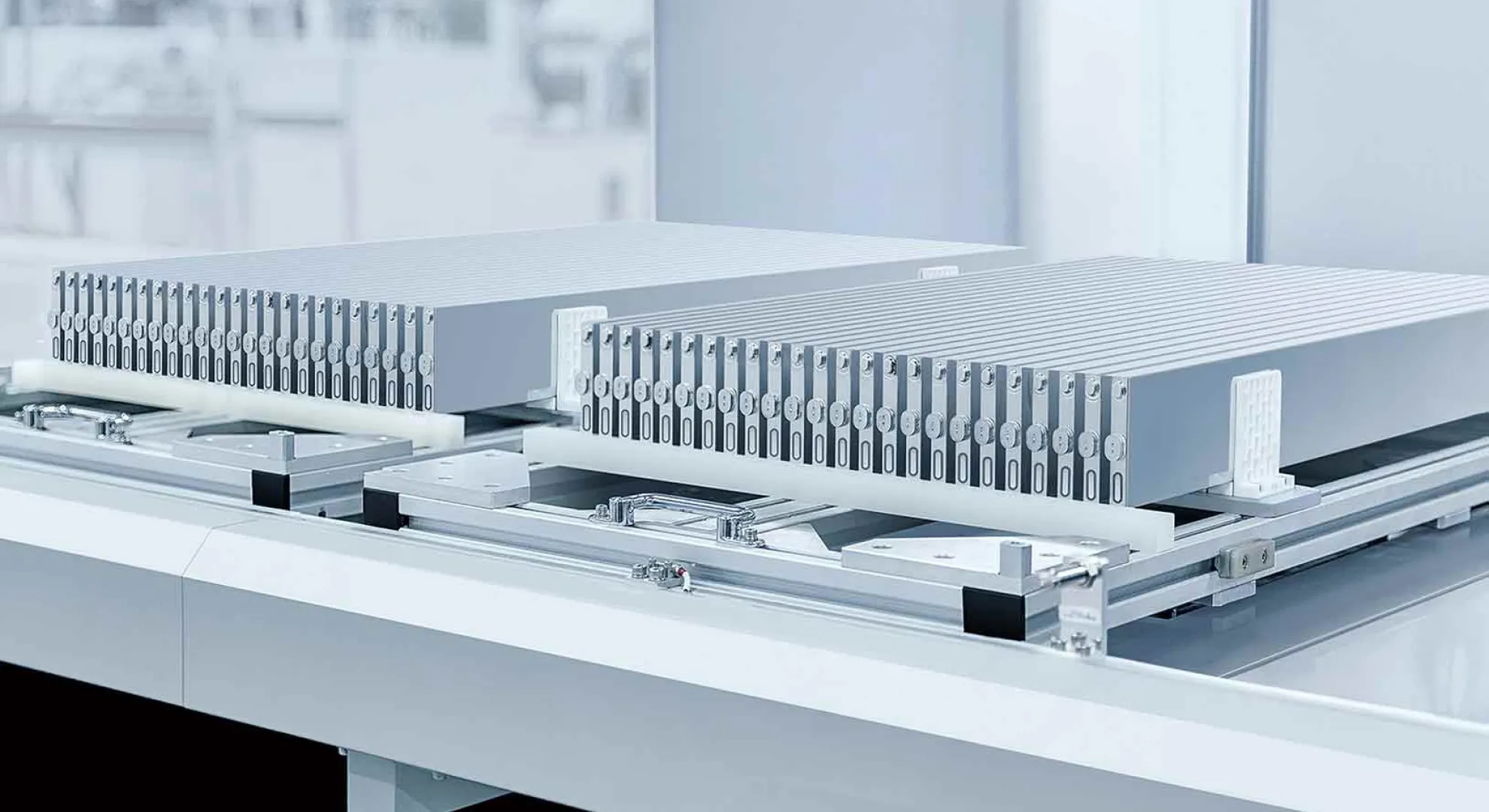

In the current year, Attero processed close to 148,000 tonnes of material annually, including e-waste and lithium-ion batteries, and expects to cross 250,000 tonnes per annum. On the lithium-ion battery side alone, its capacity is 17,500 tonnes, with plans to scale up to 60,000 tonnes as end-of-life volumes rise quarter by quarter.

Why Geopolitics and Policy Are Fueling Recycling Momentum

The acceleration in battery recycling is being driven by a convergence of structural forces. A major factor is the global push for self-reliance in critical minerals, as materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel account for a large share of battery costs and remain exposed to geopolitical and supply-chain risks.

India’s Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework is another crucial catalyst. EPR places responsibility on manufacturers to manage products throughout their entire lifecycle, reinforcing the shift toward a circular economy.

According to Vasudha Madhavan, Founder and CEO of Ostara Advisors, the most durable margins in battery recycling come from EPR-linked processing fees and recovered materials. Processing and EPR fees are contract-backed and recurring, while recovered metals benefit from India’s long-term battery demand and dependence on imports.

The Economics of Recycling and Second-Life Batteries

BatX’s Utkarsh Singh explains that battery recycling can be economically viable even without subsidies, but EPR plays a stabilising role in what is otherwise a volatile market. Effective EPR enforcement can add around 6–7 percent to EBITDA, significantly supporting scale-up efforts.

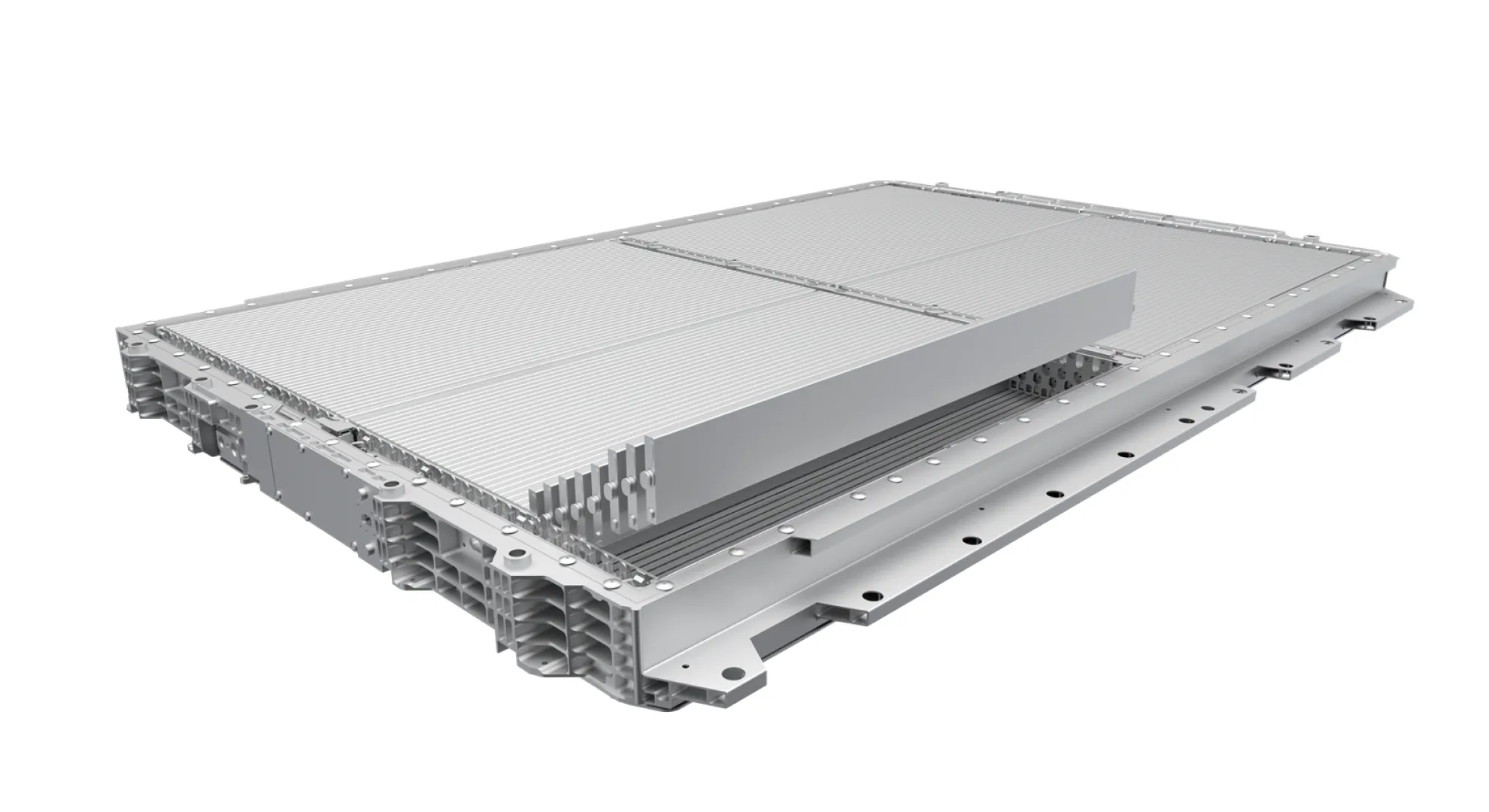

Second-life battery applications, such as stationary energy storage for telecom towers or renewable energy systems, offer higher gross margins per usable kilowatt-hour. However, these opportunities come with higher risks due to testing requirements, integration challenges, and increased working capital needs, making them less predictable at scale compared to recycling.

What Will Determine Sustainable Scale-Up

As India’s EV fleet matures, recyclers are racing to align capacity with the staggered arrival of end-of-life batteries. The sector’s long-term success will depend on consistent EPR enforcement, clear battery traceability norms, and the ability to balance heavy capital investment with long-gestation returns.

If these elements fall into place, EV battery recycling could become one of India’s most strategic clean-tech industries, reducing import dependence while closing the loop on the country’s rapidly expanding electric mobility ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q. What is driving the growth of EV battery recycling in India?

- The main drivers are rising EV adoption, upcoming end-of-life battery volumes, EPR regulations, the need for critical mineral self-reliance, and growing demand for recycled battery materials.

Q. Which EV segment will contribute the most to early recycling volumes?

- Electric two-wheelers are expected to contribute first due to their large installed base, followed by commercial four-wheelers. In the long term, buses and heavy commercial vehicles will generate the largest battery volumes.

Q. How important is EPR for battery recyclers?

- EPR is critical as it provides recurring, contract-backed revenue through processing fees and can add 6–7 percent to EBITDA, helping stabilise margins and support capacity expansion.

Q. What materials are recovered from recycled EV batteries?

- Recyclers recover lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, graphite, and other metals, many of which can be processed to battery-grade quality and reused in new cells.

Q. Are second-life EV batteries more profitable than recycling?

- Second-life applications can offer higher margins per usable kilowatt-hour, but they involve higher operational and working capital risks, making large-scale deployment less predictable than recycling.